原标题:Chinese Scientist Who Gene-Edited Babies Is Sent to Prison

原作者:By Philip Wen in Beijing and Amy Dockser Marcus in Boston

原刊于:Wall Street Jouranl

The scientist who created the world’s first known genetically modified babies, stunning the global scientific community, has been sentenced by a Chinese court to three years in prison, state media reported.

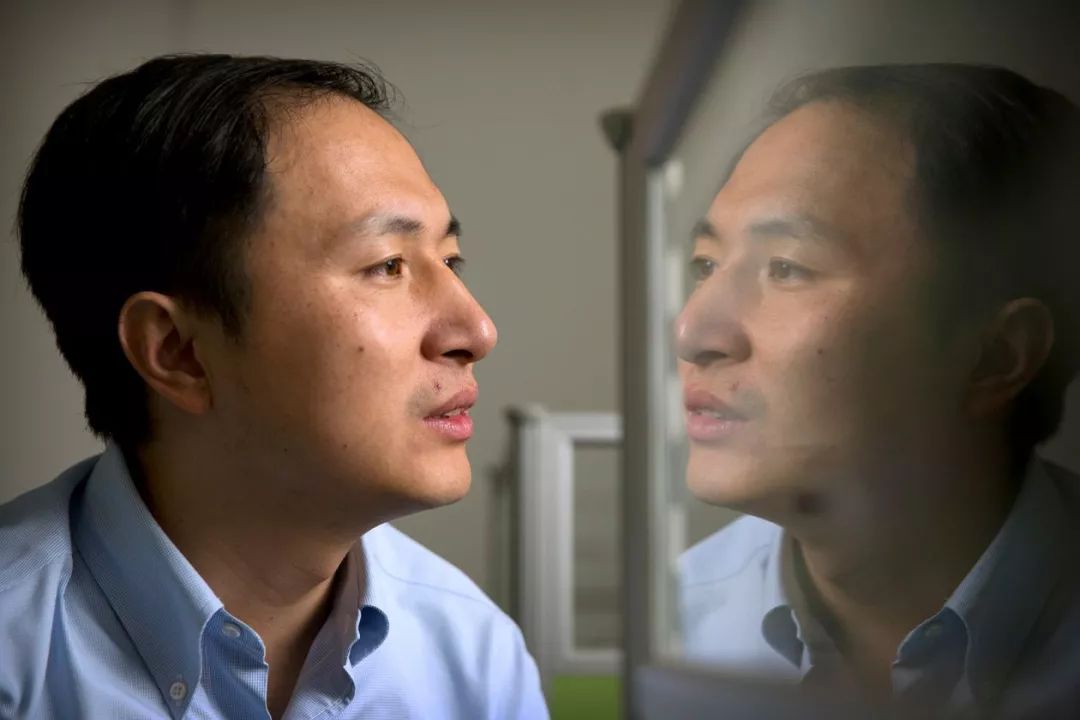

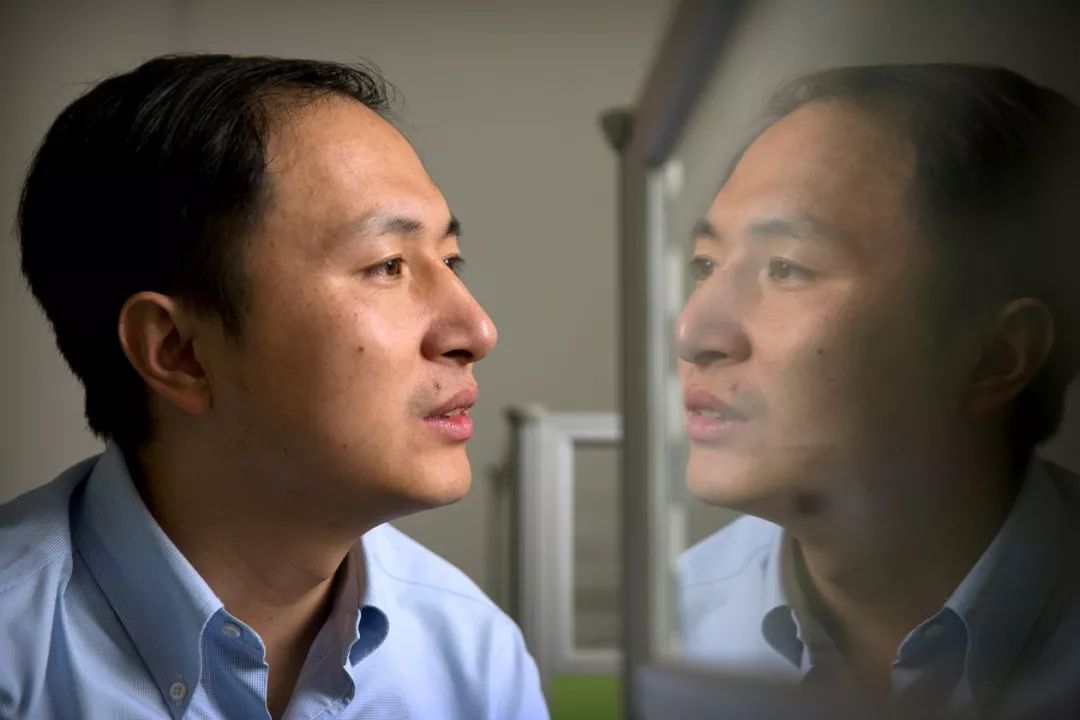

He Jiankui said in November last year he had engineered twin girls—offspring of a healthy mother and an HIV-positive father—to be resistant to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, using a nascent gene-editing technology called Crispr-Cas9.

China was able to race ahead of the U.S. on testing gene-editing technology because it had few regulatory hurdles to human trials, while the U.S. has stringent rules.

But Dr. He’s revelation drew immediate condemnation from bioethicists and fellow scientists in China and beyond, including the inventors of the gene-editing technology. Chinese authorities said last January they were investigating Dr. He, and he was fired from his post as an associate professor at Southern University of Science and Technology, based in the southern city of Shenzhen.

On Monday, a Shenzhen court convicted Dr. He and two others on charges of illegally practicing medicine related to carrying out human-embryo gene-editing intended for reproduction, the official Xinhua News Agency reported.

The court said Dr. He hoped to profit by commercializing the technology and that he forged documents and concealed the true nature of the procedures from both the patients he recruited and doctors who performed them, according to Xinhua. The report said all three defendants pleaded guilty.

“In order to pursue fame and profit, they deliberately violated the relevant national regulations, and crossed the bottom lines of scientific and medical ethics,” the court said, according to the report.

Dr. He also received a lifetime ban from working in the field of reproductive life sciences and from applying for related research grants, Xinhua said, citing local health and science authorities.

Dr. He couldn’t be reached for comment, and his lawyer couldn’t immediately be reached. A former spokesman for Dr. He didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Gene editing of embryos is taking place for research purposes in countries including the U.S. and the U.K., in lab settings. Scientists have said they are unaware of any current efforts involving gene editing of embryos for implantation and birth. But policy experts and scientists expect it will happen.

“Some scientists have announced their wish to edit the genome of embryos and bring them to term,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization’s Director-General, told the WHO expert advisory committee examining governance and oversight of human genome editing, earlier this year. WHO has announced plans for a global registry to list clinical trials involving human genome editing as a way to track research.

“WHO recommends that regulatory authorities in all countries should not allow any further work in this area until its implications have been properly considered,” said a spokesperson for WHO.

Editing the genes of embryos is considered more contentious than editing those of terminally ill patients because any changes would pass on to future generations. Unintended consequences might not surface for several years, meaning a tiny blip could have far-reaching effects.

In what turned out to be one of his last public appearances in November last year, the Chinese scientist sprang another surprise at a scientific conference in Hong Kong, announcing a second woman was pregnant with a gene-edited baby.

Monday’s Xinhua report confirmed the birth of a third gene-edited baby from a second pregnancy but provided no other details. Previous state-media reports had said the newborn twins and people involved in the second pregnancy would be monitored by government health departments.

Dr. He, the son of rice farmers, graduated with a physics undergraduate degree in China and got a doctorate from Rice University, before switching to studying biology.

As earlier reported by The Wall Street Journal, people who know Dr. He have said he wanted to make history and address what he saw as an injustice in China against HIV-positive people, who are barred from getting fertility treatments. They said Dr. He had expected plaudits from Beijing for helping in its goal of making China a force in genetic science.

In much of the Western world, it is illegal to implant a genetically modified human embryo. The U.S. forbids the Food and Drug Administration, whose signoff is needed for such an experiment, from considering it. China doesn’t have a law, and although a 2003 guideline prohibited the genetic manipulation of human embryos, it didn’t outline penalties. In February, China’s National Health Commission drafted new rules governing “high-risk” biotechnology, including gene-editing, that would introduce criminal charges and lifetime research bans if breached, but they have not come into effect.

Victor Dzau, president of the U.S. National Academy of Medicine, one of the conveners earlier this year of the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing, said the jail sentence for Dr. He and his colleagues will “have a big effect globally on all scientists.” Not all governments have policies regarding the editing and implantation of human embryos, he said. “The scientists don’t know how their government will respond,” said Dr. Dzau.

The commission is trying to create suggested guidelines and advice for scientists, clinicians and governments regarding human embryo gene editing. Some countries, Dr. Dzau added, may eventually conclude that human genome editing in embryos is acceptable under certain circumstances such as preventing lethal disease, and move forward. “Then it is up to each country,” he said. “Some decisions may be culture-dependent.”

“In the United States, everybody realizes this is something we should not do at this time. It is irresponsible until we have good guidance,” he said.

Kiran Musunuru, an associate professor of cardiovascular medicine and genetics at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of a recent book about Crispr and the gene-edited babies, said the jail sentence is likely to have a deterrent effect on scientists in China. “This is a signal that China is serious about restricting this sort of research and clamping down on rogue actors like He,” he said. “What happens behind closed doors is hard to know, but outwardly at least, they have taken a serious stance.”

Dr. Musunuru said that he believes gene editing involving patients with life-threatening diseases will continue, and so will clinical trials in such cases, which have a clear regulatory framework in the U.S.

Jennifer Doudna, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and one of the Crispr inventors, said in addition to the ethical problems involved in Dr. He’s experiment, there are also scientific ones. “We don’t have the ability to control the editing outcomes in a way that would be safe in embryos right now,” said Dr. Doudna.

Regarding the specific gene-editing changes made in the embryos, “We don’t really know what was done,” she said. “From the data presented, it looks as though the edits made were not the ones that were intended. It is very difficult to know how those edits will in fact affect the health outcomes of these kids.”

Scientists are uncertain about how the children will be monitored, their health-care needs, if the experiment harmed them, or what will happen to them in the future.

Dr. Doudna said she supports efforts by the international scientific community to discuss not only the technology but the social, ethical and technical challenges. “To me, the big question is not will this ever be done again. I think the answer is yes. The question is when, and the question is how.”

LAB + 外刊年报

本文源自微信公众号:LABcircle