圣诞假期班基本都结束了。

这个行当最幸运的是,会遇到已经或者未来会变得很优秀的学习者。

有同学能力很好了;

也有同学很努力的完成任务;

也有同学兼而有之。

有个感慨吧,我们不管是10几,还是20几的年纪,当别人说你天赋好,或者能力好的时候,别太当真。

还有人往这个角度夸你,要么是人家客气,要么是你还没进入到真正好的平台:当周围都是优秀的人的时候,没人再夸你天赋了,你也不会意识到自己的天赋。

年少时候我也觉得自己的语言天赋好。但是现在回头,我在语言学习上是花了很多的时间的。

天赋和努力可能是个永恒的话题。

两个都是主观词,所以当我们聊天赋或者聊努力的时候,可能聊的都不是同一个概念:

有的同学觉得自己每天花4个小时学习已经很努力了;有的觉得8个小时还是不够努力。

有的觉得拿个市的比赛冠军已经很有天赋了;有的觉得拿个全国的都不敢说自己有天赋。

另外,天赋和努力其实不矛盾。

有天赋的人,会更容易建立成就感,更容易坚持和努力;

努力的人,会慢慢发现自己超越了周围的人,有了“天赋”的光环。

下面一篇文章观点和我前面说的会有些不同。

世俗意义上来说,我们更愿意接受天道酬勤。 有很多的作品也是鼓励说,努力的人更有可能获得成绩。但是科学研究也显示,勤能补拙,但是能补的拙是有限的。

天赋真的很重要。能让生活少很多烦恼。

只是别误会了,这是肯定了天赋,不是肯定了我们可以不去努力了。我们可能没有自己想象的那么有天赋。

那么,当我们客观上不确定自己的天赋的时候,烦请主观上和客观上都好好的努力下。

以下是全文

原标题:Sorry, Strivers: Talent Matters

原作者:DAVID Z. HAMBRICK and ELIZABETH J. MEINZ

原刊于:New York Times

HOW do people acquire high levels of skill in science, business, music, the arts and sports? This has long been a topic of intense debate in psychology.

Research in recent decades has shown that a big part of the answer is simply practice — and a lot of it. In a pioneering study, the Florida State University psychologist K. Anders Ericsson and his colleagues asked violin students at a music academy to estimate the amount of time they had devoted to practice since they started playing. By age 20, the students whom the faculty nominated as the “best” players had accumulated an average of over 10,000 hours, compared with just under 8,000 hours for the “good” players and not even 5,000 hours for the least skilled.

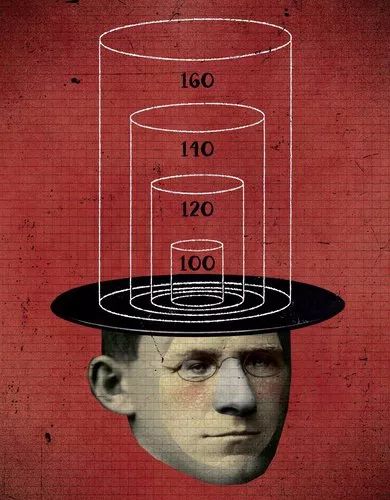

Those findings have been enthusiastically championed, perhaps because of their meritocratic appeal: what seems to separate the great from the merely good is hard work, not intellectual ability. Summing up Mr. Ericsson’s research in his book “Outliers,” Malcolm Gladwell observes that practice isn’t “the thing you do once you’re good” but “the thing you do that makes you good.” He adds that intellectual ability — the trait that an I.Q. score reflects — turns out not to be that important. “Once someone has reached an I.Q. of somewhere around 120,” he writes, “having additional I.Q. points doesn’t seem to translate into any measureable real-world advantage.”

David Brooks, the New York Times columnist, restates this idea in his book “The Social Animal,” while Geoff Colvin, in his book “Talent Is Overrated,” adds that “I.Q. is a decent predictor of performance on an unfamiliar task, but once a person has been at a job for a few years, I.Q. predicts little or nothing about performance.”

But this isn’t quite the story that science tells. Research has shown that intellectual ability matters for success in many fields — and not just up to a point.

Exhibit A is a landmark study of intellectually precocious youths directed by the Vanderbilt University researchers David Lubinski and Camilla Benbow. They and their colleagues tracked the educational and occupational accomplishments of more than 2,000 people who as part of a youth talent search scored in the top 1 percent on the SAT by the age of 13. (Scores on the SAT correlate so highly with I.Q. that the psychologist Howard Gardner described it as a “thinly disguised” intelligence test.) The remarkable finding of their study is that, compared with the participants who were “only” in the 99.1 percentile for intellectual ability at age 12, those who were in the 99.9 percentile — the profoundly gifted — were between three and five times more likely to go on to earn a doctorate, secure a patent, publish an article in a scientific journal or publish a literary work. A high level of intellectual ability gives you an enormous real-world advantage.

In our own recent research, we have discovered that “working memory capacity,” a core component of intellectual ability, predicts success in a wide variety of complex activities. In one study, we assessed the practice habits of pianists and then gauged their working memory capacity, which is measured by having a person try to remember information (like a list of random digits) while performing another task. We then had the pianists sight read pieces of music without preparation.

Not surprisingly, there was a strong positive correlation between practice habits and sight-reading performance. In fact, the total amount of practice the pianists had accumulated in their piano careers accounted for nearly half of the performance differences across participants. But working memory capacity made a statistically significant contribution as well (about 7 percent, a medium-size effect). In other words, if you took two pianists with the same amount of practice, but different levels of working memory capacity, it’s likely that the one higher in working memory capacity would have performed considerably better on the sight-reading task.

It would be nice if intellectual ability and the capacities that underlie it were important for success only up to a point. In fact, it would be nice if they weren’t important at all, because research shows that those factors are highly stable across an individual’s life span. But wishing doesn’t make it so.

None of this is to deny the power of practice. Nor is it to say that it’s impossible for a person with an average I.Q. to, say, earn a Ph.D. in physics. It’s just unlikely, relatively speaking. Sometimes the story that science tells us isn’t the story we want to hear.

要再认真一些,

这样当年纪再大一些的时候,

哪怕还是碌碌无为,

也不会太责怪自己。

LAB + 外刊年报

本文源自微信公众号:LABcircle