当人们抱怨工作忙碌,特别是相对高薪人群抱怨的时候,周围人可能大多会冷眼旁观。

但研究显示,人们是愿意为了舒适的生活节奏,牺牲一些收入的。

IMF (国际货币基金组织)在日本做的一个调查显示,年收入在$27,600或更高的人群是愿意让自己的年薪减半,来避免每个月要加班45小时以上的工作安排的。

那为什么现实生活里放弃高薪,回归生活的人那么少呢?

个人感觉上面的调查其实设置了一个非现实的情况,即,人们是明确的知道减少上班时间以后的后果的,也就是调查对象明确的清楚自己会减少一半的收入。

但是现实场景是怎样的呢?

你和你老板说,愿意少点收入,但是多点自己的时间。老板说可以,然后你就越来越被边缘化。最后收入不是减半。而是彻底没了。

所以如果我们的工作岗位替代性是比较强的话,我们是不敢去不努力的,只能加班。不是怕失去一些收入,而是不知道自己会失去的是什么。

未知,总是让人恐惧的。

文章里面另外一个有意思的是提到了各国人的上班时间。

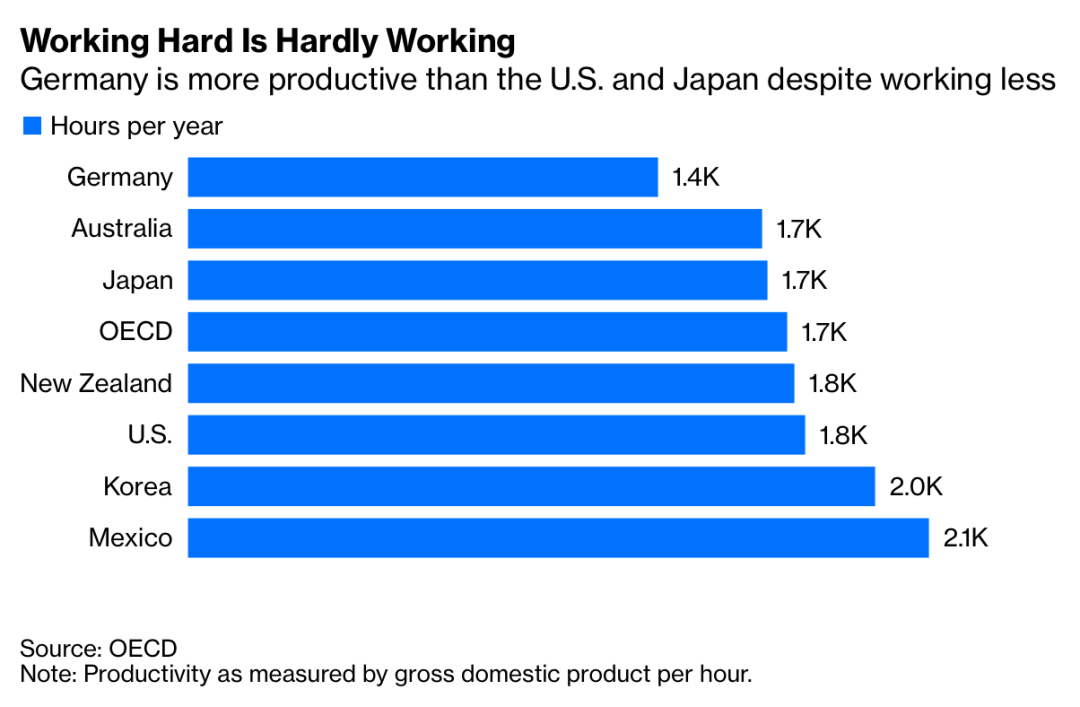

从图表来看,德国人一年工作1400个小时,最少。而我们的邻国,韩国,是每年工作2000个小时,算是比较多的了。

遗憾的是表单里面没有对于中国的数据。但我们可以自己算一下。

一年365天,去掉52个周末,104天(假设是双休)。再去掉2019年中国大陆的法定假日时间11天,所以还有250天我们是在工作的。

所以,韩国的这个一年工作2000个小时的意思,就是差不多我们每天工作8个小时(传说中的朝九晚五)。这么一想,我们大多数人一年的工作时间肯定超过2000 小时了。

另外一个表格是关于男女收入差距的:东方的几个国家(日本、韩国)男女收入差距明显大于其他国家。

🤔脸

原标题:How Much Would You Pay to Work Less?

原作者:Rachel Rosenthal

原刊于:Bloomberg

Companies from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to Monsanto Co. have gotten serious about making work more flexible. Thanks to apps and gadgets, you can easily tap away from a living-room couch, the bleachers at your son’s soccer game or huddled over a coconut on your Christmas vacation. There’s a hidden cost to all this for women, though – and it isn’t just the prospect of being available around the clock.

A recent working paper from the International Monetary Fund measured how much salary Japanese employees would be willing to forgo to enjoy a healthier work-life balance. It found that earners making 3 million yen ($27,600) a year would give up nearly half of their income to avoid putting in 45 hours or more of overtime per month. That outcome was roughly consistent with higher-wage workers, too.

The most obvious takeaway would be that companies should do everything they can to keep hours reasonable. It doesn’t take an MBA to see that lower salaries would improve the bottom line, with the added upside of happier and possibly more productive workers. There’s an important caveat, however: Women are much more eager than men to give up money for time. That mostly comes down to deeper feelings of guilt, according to the paper, not just for child-rearing but also general household responsibilities such as cooking and caring for aging parents.

While this conclusion isn’t revolutionary, the policy implications are stark. For every woman who is willing to accept less money for more flexibility, there’s someone out there inclined to put in that 14-hour day at a desk. This suggests that companies eager to give women more choice by offering a four-day week or shorter hours, may wind up inadvertently deepening gender pay gaps. The better way to protect work-life balance, then, is to make sure all employees – male, female, young, old, parents and the childless – are spending fewer, more productive hours on the clock.

There’s ample research to show that working more doesn’t necessarily produce better results. In fact, productivity drops off when employees work more than 50 hours a week, according to a Stanford University study. Whether you work 70 hours or 56 hours, output is roughly the same.

Despite Japan’s reputation for burning the midnight oil, Americans work even more: 1,786 hours per year compared with 1,680, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Germany works the fewest at 1,363. Yet Germany is the most productive of the three, as measured by gross domestic product per hour, followed by Japan, then the U.S.

The good news is that employers are starting to respond. In August, Microsoft Corp. tested out a four-day work week in its Japan locations. Productivity rose 40% from a year earlier. One local-government office in downtown Tokyo resorted to shutting off the lights at 7 p.m. to force people to go home. And in Europe, financial industry groups are pressing the London Stock Exchange to cut its trading day by 90 minutes.

All this awareness is a good thing; employers and policymakers just need to recognize the pitfalls. The most troubling element of the IMF paper may have been women’s willingness to make less in a country where the pay gap is already so wide. The median income for Japanese men is 24.5% higher than for men and women. That compares with an average of 13.5% in the OECD and 18.2% in the U.S.

Flexible working can mean a lot of things: telecommuting, shorter work weeks, or even the ability to set a fluid schedule, so long as you hit a certain number of hours. These options benefit men and women alike. I can’t think of a single parent who doesn’t appreciate the ability to stay on top of emails while sitting in the waiting room at the pediatrician.

But what if all that multitasking only adds hours and stress? At a previous job, when my son was a baby, I was able to leave the office early to put him to bed. Yet I recall many nights spent staring into the white halo of my iPhone, crafting emails with one finger, and nursing him in the crook of my spare arm. I probably would have been willing to give up a fair chunk of salary to guiltlessly complete that work in the morning – and could have finished it quicker, to boot. Many women are wary of flexible schedules for this precise reason: They know they’ll end up working for free. Even companies with the best intentions will have difficulty accounting for an evolving definition of what constitutes time spent on the job.

That’s why flexible HR policies are meaningless if culture doesn’t evolve more quickly. Japanese employees get some of the most generous family-leave packages in the world, yet few fathers take advantage of them, as my colleague Anjani Trivedi has noted. People there are literally working themselves to death with 100-hour weeks.

Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of Panasonic Corp. and business-management guru, said you should think of your career as a “three-day chore” — that is, approach simple tasks with the sincerity of a lifelong occupation. It’s about time we bring as much commitment to protecting our well-being.

本文源自微信公众号:LABcircle